Presentation for In Form Symposium 19/8/

I began a full time doctorate through the School of Design, University of Technology, Sydney, in March this year. This is a presentation of the early stages of my research design.

For me, returning to full-time study from practice was problematic; do you have to sacrifice designing to be a design theorist? I wasn’t prepared to give up my practice entirely to pursue research. So discovering post-graduate research that involves ‘making’ was central to my decision to return to university. A full-time practice-led doctorate provides an opportunity to develop as a designer by reflecting on the process of a specific design practice, in my case, book design. As a design practitioner, I can provide insights – through reflection and articulation of the design process – that non-practicing theorists cannot.

This symposium, and other current discussions, demonstrates that rigorous debate surrounds what can and cannot be considered practice-led research. To complicate matters, what can and cannot be considered a practice-led doctorate is even more indistinct. Currently, a practice-led doctorate involves actively addressing this distinction. As a working definition (and I recognise this is by no means the only – or even necessarily a successful – model) I propose that my research:

1. Originate from an issue identified through practice;

2. Include a contextual survey and literature review (analytical component);

3. Involve ‘making’ as investigation (generative component);

4. Articulate: the process of making, reflections on significant shifts/discoveries and point to sociological/industry impact of the research

5. Present this articulated reflective process in an appropriate form.

I recognise that design is an iterative process; it involves cycles of making, critiquing, reflecting and refining. I expect to work back and forth around points 2, 3 and 4, but I cannot predict how this will happen until I actually begin designing.

1. Identifying an issue in practice

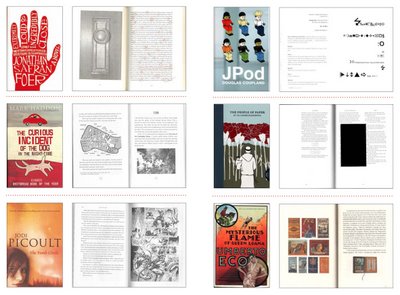

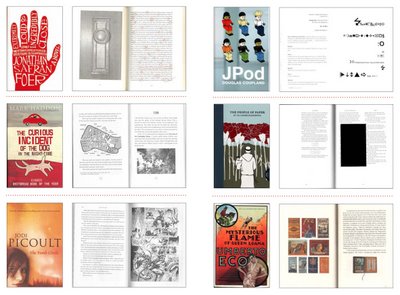

While working in-house at a publishing company, I noticed contemporary fiction using graphic elements in experimental ways was becoming increasingly more common. Some examples of these books are shown here :

I want to make clear that these are not graphic novels, or childrens' fiction. The images appear sporadically, scattered through a traditional looking novel. Most readers wouldn’t be aware that these books contain images until they stumble upon them. As such, this is not a new genre that requires a new section in bookstores. Rather, it’s a way of using graphic elements as a literary device within fiction.

I want to make clear that these are not graphic novels, or childrens' fiction. The images appear sporadically, scattered through a traditional looking novel. Most readers wouldn’t be aware that these books contain images until they stumble upon them. As such, this is not a new genre that requires a new section in bookstores. Rather, it’s a way of using graphic elements as a literary device within fiction.

Books that use graphic elements as a literary device are not a new phenomenon:

In fact, it could be easily argued that historically, books have been more heavily illustrated than they are today. However, these illustrations have generally been decorative embellishments, rather than conscious interruptions, to the written text.

In fact, it could be easily argued that historically, books have been more heavily illustrated than they are today. However, these illustrations have generally been decorative embellishments, rather than conscious interruptions, to the written text.

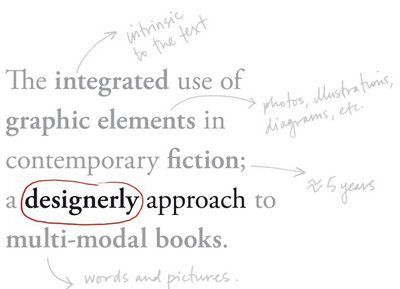

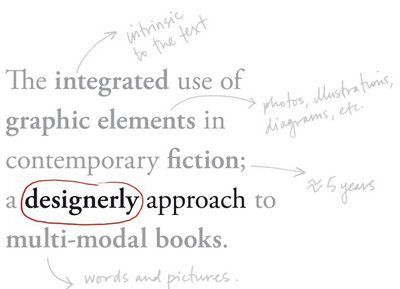

Which leads me to my topic:

The integrated use of graphic elements in contemporary fiction; a designerly approach to multi-modal books.

To break down my terms:

Graphic elements may be photographs, illustrations, diagrams, experimental typography.

By the integrated use of these elements, I mean rather than examining books using graphic elements simply as illustrations of the text, or as a parallel narrative approach (such as comics, graphic novels, picture books), I am interested in books using graphic elements in a manner intrinsic to the writing; where the visual does something more than simply reflecting the text.

Contemporary fiction, here, means popular or literary fiction published in the past five years (this is not a strict definition, rather an attempt to manage the scope of my inquiry).

Multi-modal refers to more than one mode of communication (a graphic mode and written mode) combined in a single form (a book).

Finally, the designerly approach takes a little more explaining. Studies around post-modern fiction and Semiotics have interrogated similar text-image relationships, but primarily from the perspective of the text, rather than the image. So, I’m not focusing on why this is happening, from either an industry or cultural perspective. I’m also not focusing on how you read, or experience, these texts, though I recognise that these are both important areas of inquiry. What I am focusing on is how graphic elements are being integrated into the written text, from the perspective of those generating the text: the writer, the image-maker and the book designer.

How is this practice-led?

How is this practice-led?

I intend to investigate how this phenomenon can be examined as a way of working rather than a cultural trend; instead of arguing for the legitimacy or longevity of this narrative style (a cultural studies approach), my research will investigate experimental word-image interplay as a way of practicing (a Visual Communications approach). The body of my research will be through articulated ‘making’: to explore the potentials of a way of working, it makes sense to experiment in practice.

At this stage, I am uncertain exactly what my ‘making’ will involve. I am expecting to develop projects from the findings of my preliminary contextual survey.

2. Contextual survey (analytical component)

After developing a topic, through an issue from practice, the first problem I faced was explaining what these books were to people who hadn’t seen them. I decided to conduct a contextual survey – an analysis of existing examples – that examins both how graphic elements appear in books, and how the inclusion of these elements is perceived. The contextual survey will contain both quantitative and qualitative information, and will be presented as a series of maps rather than a written document. Notable findings may be written up as sections of the final exegesis, but much of the information will be more valuable as a visual reference than textual analysis. As such, I'm using the language of my discipline to express the scholarly research.

Aside from more formal text-image analysis, I am conducting some investigative mapping exercises as a way of researching.

1.

I began this exercise as a means of locating an appropriate label for books with integrated graphic elements. In the early stages of my research, I toyed with ‘experimental graphic novels’ (immediately implied comics, which is not what I’m looking at), ‘illustrated literature’ (which denotes picture books) and a few other inadequate combinations of words to do with illustrations and books. I decided to look at how reviewers were describing books with the graphic approach I was interested in, to see if there was a term already in use, or one I might adapt. I chose four books using graphic elements in quite different ways – Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, Umberto Eco’s The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana, Jodi Picoult’s The Tenth Circle – and sourced ten reviews of each book. Although the exercise was searching for an appropriate label, I realised the more interesting descriptions were actually of how the reviewer reacted to the images being included in the first place. To analyse this in a way that allowed me to compare and contrast descriptions of one particular book, but also compare each book with the others, I developed visual maps. I streamed the text of the ten reviews of each book into a single document, then highlighted, in colour, how the critic has described: a) the format; b) the book as a whole; c) use of visual elements; d) writing style.

I began this exercise as a means of locating an appropriate label for books with integrated graphic elements. In the early stages of my research, I toyed with ‘experimental graphic novels’ (immediately implied comics, which is not what I’m looking at), ‘illustrated literature’ (which denotes picture books) and a few other inadequate combinations of words to do with illustrations and books. I decided to look at how reviewers were describing books with the graphic approach I was interested in, to see if there was a term already in use, or one I might adapt. I chose four books using graphic elements in quite different ways – Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, Umberto Eco’s The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana, Jodi Picoult’s The Tenth Circle – and sourced ten reviews of each book. Although the exercise was searching for an appropriate label, I realised the more interesting descriptions were actually of how the reviewer reacted to the images being included in the first place. To analyse this in a way that allowed me to compare and contrast descriptions of one particular book, but also compare each book with the others, I developed visual maps. I streamed the text of the ten reviews of each book into a single document, then highlighted, in colour, how the critic has described: a) the format; b) the book as a whole; c) use of visual elements; d) writing style.

I can easily see repeated phrases or sentiments within each map, or line the maps up to compare how different books are discussed.

At this stage, I haven’t discovered what I was looking for – a convenient term to describe these books. Instead, I came to the realisation that there is no term for these books because the graphics do not define a genre or format, they are an integrated literary device that can be used within almost any style of written text.

The exercise has also raised the issue of critique. Why are these books not reviewed in design magazines and journal? Why are these books reviewed almost exclusively by wordsmiths rather than image-makers? Why are the graphic elements not being analysed in terms of how they affect the narrative? It sounds obvious now, but from this, I reconsidered my audience. Where I was initially so determined to focus on the ‘designerly’ aspect of my research, I forgot the value it may have for writers and publishers, as well as designers and design academics.

2.

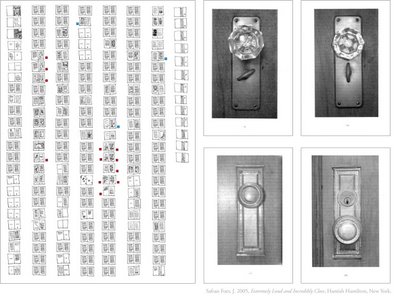

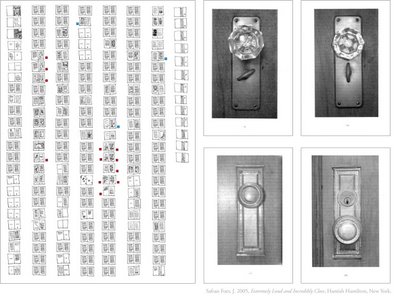

In another investigative exercise, I intended to find patterns in where the graphic elements occur and get a sense of rhythm by thumbnailing each book. This is obviously an exercise in deconstruction, reversing the design process in an attempt to understand how the designer has put the book together, but more importantly, it is also a method which forces me examine the books more analytically. As a designer, sketching is a natural way of thinking images through. By committing pen to paper, I force myself to deeply analyse what an image may represent, rather than relying on what I have taken it to be on first glance.

In another investigative exercise, I intended to find patterns in where the graphic elements occur and get a sense of rhythm by thumbnailing each book. This is obviously an exercise in deconstruction, reversing the design process in an attempt to understand how the designer has put the book together, but more importantly, it is also a method which forces me examine the books more analytically. As a designer, sketching is a natural way of thinking images through. By committing pen to paper, I force myself to deeply analyse what an image may represent, rather than relying on what I have taken it to be on first glance.

The illustration above shows the thumbnailed spreads of Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. Throughout the novel, a full-page image of a doorknob appears several times. When I read the book, I assumed this was the same photograph repeated – an easy enough mistake if you look at how many pages divide each appearance of the image – but while drawing the thumbnails, I realised they were actually all different, which significantly alters my reading of this visual allegory in the context of the book. I may have noticed this in future readings anyway, but the act of replicating the images forced me to look at them with more critical eyes.

Again, the purpose of these mapping exercises is not to argue the cultural validity or commercial longevity of these multi-modal works of fiction, rather I’m saying: here is a list of examples; this is how they work; and here is how they are being critiqued. Through comparing and contrasting the maps I will produce for a range of books, I will identify issues of interest around the integration of graphic elements in works of fiction. This will inform the practice-led component of my research. I’m not sure what these issues or questions will be at this stage, and I won’t have a strong idea until I progress through this phase of my contextual survey.

I intend continue the contextual survey for the duration of the research, but at some stage it will need to recede to the background as I focus on generative practice.

So far, I’ve discussed how I am using my tools as a design practitioner to both investigate and then present the results of that investigation. Now, I’m going to address a different kind of practice.

3. ‘Making’ as investigation

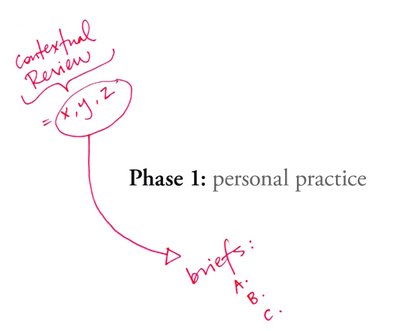

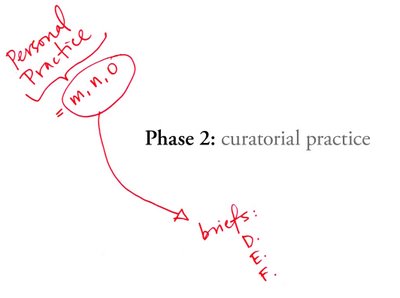

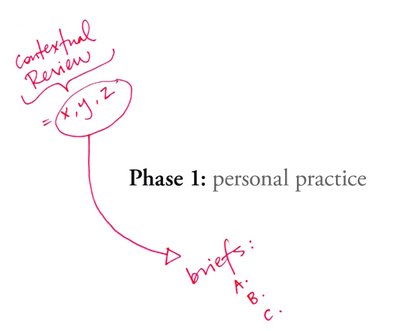

The generative component of my research will occur in two phases:

To respond to questions generated by the contextual survey, I will create briefs to test – by designing – and reflect on my design process.

To respond to questions generated by the contextual survey, I will create briefs to test – by designing – and reflect on my design process.

Some examples may be:

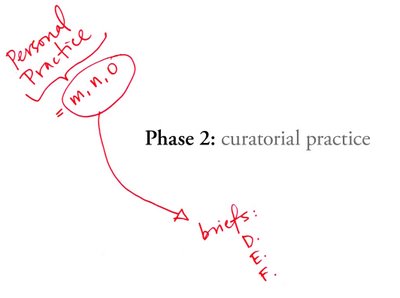

Based on my reflections from the first generative phase, I will write briefs for others to respond to. I will document and reflect on their process, their results, and their personal reflections. This allows me to investigate the intuitive practice of multiple designers (and writers), rather than relying on my personal perspective as a writer/designer. These ‘case studies’ will provide a rich counterpoint to my own reflective practice.

Based on my reflections from the first generative phase, I will write briefs for others to respond to. I will document and reflect on their process, their results, and their personal reflections. This allows me to investigate the intuitive practice of multiple designers (and writers), rather than relying on my personal perspective as a writer/designer. These ‘case studies’ will provide a rich counterpoint to my own reflective practice.

At this stage, possible projects might be:

4/5. Articulation and presentation in appropriate form

At this early stage of my research, I am lumping stages 4 and 5 together because I am not yet able to discuss them in depth. Anticipating how I will articulate my reflections before I have made them, or how I will present my content before it exists, would be to unnecessarily limit the potentials of this doctorate.

However, these will be crucial stages in defining my work as research, rather than experimental practice. Articulation, in my case through an artefact, distinguishes research from practice; making the process and reflective practice visible renderes this project a valuable resource for other designers and academics.

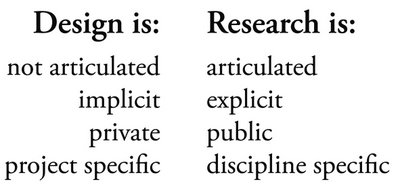

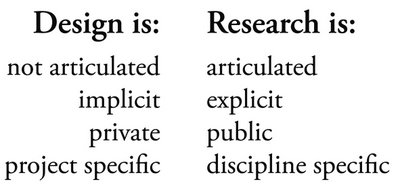

So, to set a simple dichotomy between practice and research:

This is not to say that design practitioners are not reflective or articulate. Rather, that as a practitioner, your reflections are implicit, private, contributing to your own tacit knowledge – your creative instinct, or designer’s eye. On the other hand, the aim of research is to publicly contribute to the body of knowledge within the design discipline, to make process and reflection explicit.

This is not to say that design practitioners are not reflective or articulate. Rather, that as a practitioner, your reflections are implicit, private, contributing to your own tacit knowledge – your creative instinct, or designer’s eye. On the other hand, the aim of research is to publicly contribute to the body of knowledge within the design discipline, to make process and reflection explicit.

At this stage, I will present my research as a book containing:

Documentation of research process

Documentation of design projects

Articulation of reflections

Articulation of projections

The book itself will be designed using visual elements as narrative and documentary devices, so the final artefact contains my academic argument in both a scholarly and designerly manner. My doctorate will have both a practice outcome and a research outcome, providing a case study for both design practice and design research.

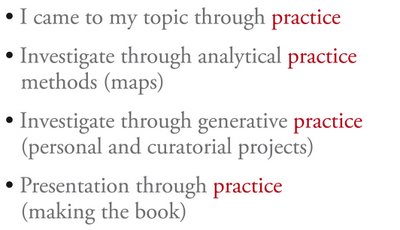

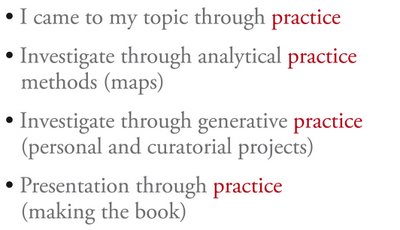

Presently, I am still not certain how to locate my research as specifically practice-led; there is no single moment where practice becomes central. Rather, the practice is evident/evolving in several ways:

As a designer, my practice informs the way I interact with and understand my world. With this in mind, it should come as no surprise that practice appears everywhere in this research project.

As a designer, my practice informs the way I interact with and understand my world. With this in mind, it should come as no surprise that practice appears everywhere in this research project.

For me, returning to full-time study from practice was problematic; do you have to sacrifice designing to be a design theorist? I wasn’t prepared to give up my practice entirely to pursue research. So discovering post-graduate research that involves ‘making’ was central to my decision to return to university. A full-time practice-led doctorate provides an opportunity to develop as a designer by reflecting on the process of a specific design practice, in my case, book design. As a design practitioner, I can provide insights – through reflection and articulation of the design process – that non-practicing theorists cannot.

This symposium, and other current discussions, demonstrates that rigorous debate surrounds what can and cannot be considered practice-led research. To complicate matters, what can and cannot be considered a practice-led doctorate is even more indistinct. Currently, a practice-led doctorate involves actively addressing this distinction. As a working definition (and I recognise this is by no means the only – or even necessarily a successful – model) I propose that my research:

1. Originate from an issue identified through practice;

2. Include a contextual survey and literature review (analytical component);

3. Involve ‘making’ as investigation (generative component);

4. Articulate: the process of making, reflections on significant shifts/discoveries and point to sociological/industry impact of the research

5. Present this articulated reflective process in an appropriate form.

I recognise that design is an iterative process; it involves cycles of making, critiquing, reflecting and refining. I expect to work back and forth around points 2, 3 and 4, but I cannot predict how this will happen until I actually begin designing.

1. Identifying an issue in practice

While working in-house at a publishing company, I noticed contemporary fiction using graphic elements in experimental ways was becoming increasingly more common. Some examples of these books are shown here :

I want to make clear that these are not graphic novels, or childrens' fiction. The images appear sporadically, scattered through a traditional looking novel. Most readers wouldn’t be aware that these books contain images until they stumble upon them. As such, this is not a new genre that requires a new section in bookstores. Rather, it’s a way of using graphic elements as a literary device within fiction.

I want to make clear that these are not graphic novels, or childrens' fiction. The images appear sporadically, scattered through a traditional looking novel. Most readers wouldn’t be aware that these books contain images until they stumble upon them. As such, this is not a new genre that requires a new section in bookstores. Rather, it’s a way of using graphic elements as a literary device within fiction.Books that use graphic elements as a literary device are not a new phenomenon:

In fact, it could be easily argued that historically, books have been more heavily illustrated than they are today. However, these illustrations have generally been decorative embellishments, rather than conscious interruptions, to the written text.

In fact, it could be easily argued that historically, books have been more heavily illustrated than they are today. However, these illustrations have generally been decorative embellishments, rather than conscious interruptions, to the written text.Which leads me to my topic:

The integrated use of graphic elements in contemporary fiction; a designerly approach to multi-modal books.

To break down my terms:

Graphic elements may be photographs, illustrations, diagrams, experimental typography.

By the integrated use of these elements, I mean rather than examining books using graphic elements simply as illustrations of the text, or as a parallel narrative approach (such as comics, graphic novels, picture books), I am interested in books using graphic elements in a manner intrinsic to the writing; where the visual does something more than simply reflecting the text.

Contemporary fiction, here, means popular or literary fiction published in the past five years (this is not a strict definition, rather an attempt to manage the scope of my inquiry).

Multi-modal refers to more than one mode of communication (a graphic mode and written mode) combined in a single form (a book).

Finally, the designerly approach takes a little more explaining. Studies around post-modern fiction and Semiotics have interrogated similar text-image relationships, but primarily from the perspective of the text, rather than the image. So, I’m not focusing on why this is happening, from either an industry or cultural perspective. I’m also not focusing on how you read, or experience, these texts, though I recognise that these are both important areas of inquiry. What I am focusing on is how graphic elements are being integrated into the written text, from the perspective of those generating the text: the writer, the image-maker and the book designer.

How is this practice-led?

How is this practice-led?I intend to investigate how this phenomenon can be examined as a way of working rather than a cultural trend; instead of arguing for the legitimacy or longevity of this narrative style (a cultural studies approach), my research will investigate experimental word-image interplay as a way of practicing (a Visual Communications approach). The body of my research will be through articulated ‘making’: to explore the potentials of a way of working, it makes sense to experiment in practice.

At this stage, I am uncertain exactly what my ‘making’ will involve. I am expecting to develop projects from the findings of my preliminary contextual survey.

2. Contextual survey (analytical component)

After developing a topic, through an issue from practice, the first problem I faced was explaining what these books were to people who hadn’t seen them. I decided to conduct a contextual survey – an analysis of existing examples – that examins both how graphic elements appear in books, and how the inclusion of these elements is perceived. The contextual survey will contain both quantitative and qualitative information, and will be presented as a series of maps rather than a written document. Notable findings may be written up as sections of the final exegesis, but much of the information will be more valuable as a visual reference than textual analysis. As such, I'm using the language of my discipline to express the scholarly research.

Aside from more formal text-image analysis, I am conducting some investigative mapping exercises as a way of researching.

1.

I began this exercise as a means of locating an appropriate label for books with integrated graphic elements. In the early stages of my research, I toyed with ‘experimental graphic novels’ (immediately implied comics, which is not what I’m looking at), ‘illustrated literature’ (which denotes picture books) and a few other inadequate combinations of words to do with illustrations and books. I decided to look at how reviewers were describing books with the graphic approach I was interested in, to see if there was a term already in use, or one I might adapt. I chose four books using graphic elements in quite different ways – Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, Umberto Eco’s The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana, Jodi Picoult’s The Tenth Circle – and sourced ten reviews of each book. Although the exercise was searching for an appropriate label, I realised the more interesting descriptions were actually of how the reviewer reacted to the images being included in the first place. To analyse this in a way that allowed me to compare and contrast descriptions of one particular book, but also compare each book with the others, I developed visual maps. I streamed the text of the ten reviews of each book into a single document, then highlighted, in colour, how the critic has described: a) the format; b) the book as a whole; c) use of visual elements; d) writing style.

I began this exercise as a means of locating an appropriate label for books with integrated graphic elements. In the early stages of my research, I toyed with ‘experimental graphic novels’ (immediately implied comics, which is not what I’m looking at), ‘illustrated literature’ (which denotes picture books) and a few other inadequate combinations of words to do with illustrations and books. I decided to look at how reviewers were describing books with the graphic approach I was interested in, to see if there was a term already in use, or one I might adapt. I chose four books using graphic elements in quite different ways – Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, Umberto Eco’s The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana, Jodi Picoult’s The Tenth Circle – and sourced ten reviews of each book. Although the exercise was searching for an appropriate label, I realised the more interesting descriptions were actually of how the reviewer reacted to the images being included in the first place. To analyse this in a way that allowed me to compare and contrast descriptions of one particular book, but also compare each book with the others, I developed visual maps. I streamed the text of the ten reviews of each book into a single document, then highlighted, in colour, how the critic has described: a) the format; b) the book as a whole; c) use of visual elements; d) writing style.I can easily see repeated phrases or sentiments within each map, or line the maps up to compare how different books are discussed.

At this stage, I haven’t discovered what I was looking for – a convenient term to describe these books. Instead, I came to the realisation that there is no term for these books because the graphics do not define a genre or format, they are an integrated literary device that can be used within almost any style of written text.

The exercise has also raised the issue of critique. Why are these books not reviewed in design magazines and journal? Why are these books reviewed almost exclusively by wordsmiths rather than image-makers? Why are the graphic elements not being analysed in terms of how they affect the narrative? It sounds obvious now, but from this, I reconsidered my audience. Where I was initially so determined to focus on the ‘designerly’ aspect of my research, I forgot the value it may have for writers and publishers, as well as designers and design academics.

2.

In another investigative exercise, I intended to find patterns in where the graphic elements occur and get a sense of rhythm by thumbnailing each book. This is obviously an exercise in deconstruction, reversing the design process in an attempt to understand how the designer has put the book together, but more importantly, it is also a method which forces me examine the books more analytically. As a designer, sketching is a natural way of thinking images through. By committing pen to paper, I force myself to deeply analyse what an image may represent, rather than relying on what I have taken it to be on first glance.

In another investigative exercise, I intended to find patterns in where the graphic elements occur and get a sense of rhythm by thumbnailing each book. This is obviously an exercise in deconstruction, reversing the design process in an attempt to understand how the designer has put the book together, but more importantly, it is also a method which forces me examine the books more analytically. As a designer, sketching is a natural way of thinking images through. By committing pen to paper, I force myself to deeply analyse what an image may represent, rather than relying on what I have taken it to be on first glance.The illustration above shows the thumbnailed spreads of Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. Throughout the novel, a full-page image of a doorknob appears several times. When I read the book, I assumed this was the same photograph repeated – an easy enough mistake if you look at how many pages divide each appearance of the image – but while drawing the thumbnails, I realised they were actually all different, which significantly alters my reading of this visual allegory in the context of the book. I may have noticed this in future readings anyway, but the act of replicating the images forced me to look at them with more critical eyes.

Again, the purpose of these mapping exercises is not to argue the cultural validity or commercial longevity of these multi-modal works of fiction, rather I’m saying: here is a list of examples; this is how they work; and here is how they are being critiqued. Through comparing and contrasting the maps I will produce for a range of books, I will identify issues of interest around the integration of graphic elements in works of fiction. This will inform the practice-led component of my research. I’m not sure what these issues or questions will be at this stage, and I won’t have a strong idea until I progress through this phase of my contextual survey.

I intend continue the contextual survey for the duration of the research, but at some stage it will need to recede to the background as I focus on generative practice.

So far, I’ve discussed how I am using my tools as a design practitioner to both investigate and then present the results of that investigation. Now, I’m going to address a different kind of practice.

3. ‘Making’ as investigation

The generative component of my research will occur in two phases:

To respond to questions generated by the contextual survey, I will create briefs to test – by designing – and reflect on my design process.

To respond to questions generated by the contextual survey, I will create briefs to test – by designing – and reflect on my design process.Some examples may be:

- Asking publishers/editors I have working relationships with to consider integrating a graphic device in an upcoming project;

- Finding passages of text with a strong recurring metaphor and replacing it with a graphic device;

- Working with a writer to develop an integrated graphic device simultaneously with their writing.

Based on my reflections from the first generative phase, I will write briefs for others to respond to. I will document and reflect on their process, their results, and their personal reflections. This allows me to investigate the intuitive practice of multiple designers (and writers), rather than relying on my personal perspective as a writer/designer. These ‘case studies’ will provide a rich counterpoint to my own reflective practice.

Based on my reflections from the first generative phase, I will write briefs for others to respond to. I will document and reflect on their process, their results, and their personal reflections. This allows me to investigate the intuitive practice of multiple designers (and writers), rather than relying on my personal perspective as a writer/designer. These ‘case studies’ will provide a rich counterpoint to my own reflective practice.At this stage, possible projects might be:

- A short course through the Centre for New Writing, open to students from writing degrees and the school of design (I am drafting this course at the moment);

- Online projects pairing professional writer/designers (it may be difficult to gauge their reflective practice as many professionals don’t document this);

- Workshops and projects with local writers and designers.

4/5. Articulation and presentation in appropriate form

At this early stage of my research, I am lumping stages 4 and 5 together because I am not yet able to discuss them in depth. Anticipating how I will articulate my reflections before I have made them, or how I will present my content before it exists, would be to unnecessarily limit the potentials of this doctorate.

However, these will be crucial stages in defining my work as research, rather than experimental practice. Articulation, in my case through an artefact, distinguishes research from practice; making the process and reflective practice visible renderes this project a valuable resource for other designers and academics.

So, to set a simple dichotomy between practice and research:

This is not to say that design practitioners are not reflective or articulate. Rather, that as a practitioner, your reflections are implicit, private, contributing to your own tacit knowledge – your creative instinct, or designer’s eye. On the other hand, the aim of research is to publicly contribute to the body of knowledge within the design discipline, to make process and reflection explicit.

This is not to say that design practitioners are not reflective or articulate. Rather, that as a practitioner, your reflections are implicit, private, contributing to your own tacit knowledge – your creative instinct, or designer’s eye. On the other hand, the aim of research is to publicly contribute to the body of knowledge within the design discipline, to make process and reflection explicit.At this stage, I will present my research as a book containing:

Documentation of research process

Documentation of design projects

Articulation of reflections

Articulation of projections

The book itself will be designed using visual elements as narrative and documentary devices, so the final artefact contains my academic argument in both a scholarly and designerly manner. My doctorate will have both a practice outcome and a research outcome, providing a case study for both design practice and design research.

Presently, I am still not certain how to locate my research as specifically practice-led; there is no single moment where practice becomes central. Rather, the practice is evident/evolving in several ways:

As a designer, my practice informs the way I interact with and understand my world. With this in mind, it should come as no surprise that practice appears everywhere in this research project.

As a designer, my practice informs the way I interact with and understand my world. With this in mind, it should come as no surprise that practice appears everywhere in this research project.

Comments

Just dropped in seeing your e-mail. I'll have to add you to my list of blog-mates (will do shortly afterwards) ;-)

We managed to discuss a great deal of stuff on Satruday which was brilliant. Whilst building on what we talked about, I just wanted to comment on your project, or offer a critique, as I remember that we didn't get to talk about your work in particular / specifically. And, I guess, one of the great aspects of presenting work and building a community of practice, is to get feedback from others, so here I am!

There were some comments I hastilly jotted down during your presentation, and reading your post again, it had refreshed my memory. I have a few points to make;

I may be mis-interpreting your research, but as we know whether it is research or design, it is a discovery-led, iterative process. So, your 'distinct' chronological stages seemed to jarr from this process, especially between the stages 2, 3 and 4. I can see why you have separated them, but I believe (and from experience) that it is okay and perhaps more truer to the enqiry to jumble them up. I imagine that your research will involve cycles of making, critique, reflect and articulate, and these are not in any particular order.

I am most curious of the generative stage of your research when you are actually designing a 'multi-modal' book. I think the interesting areas for me to look out for is the negotiation that takes place stemming from HOW and WHY you design. Will you write the text, or will someone else? Who plays the role of the editor / art director? How will you define the audience? How would you evaluate the 'book's success? Are you challenging the norms of 'reading' or even what a 'book' is? Are you interrogating the normative process of designing a book? If it is not text-led (ie the text is written first), could it be visually-led (ie the visual is made first, then the text comes later). This is bit like writing songs - is it the lyrics first or the music?

Whilst doing these projects, either on your own or in collaboration with others, what will be the driver for these projects? What are you trying to 'change' or offer to others? What will be different / similar to what you will do, that Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore did? Or how SML XL: Bruce Mau collaborated with Rem Koolhaas?

You mention that you are focusing on 'how this is happening from a design perspective'. I think this needs to be clarified further. To me, it implies a sense of detachment / objectivity. How would you negotiate the relationship between the designer and what he/she designs? What is the value of the analysis of Safran-Foer's book from your perspective, to the analysis by the designer who actually designed it?

In short, one of the strength of PLR to me, is the practitioner's experience of designing. Why they did what they did, and how they did it for whom. So as my last comment, here is what I (biasedly) think would be great thing to offer the world. Show others a variety of projects that investigated how you (Zoe) designed multi-modal books. The context for how you did it and the questions you explore will obviously vary within the projects. But illuminate and arituculate how you did what you did, and why you did it. From your presentation, I sensed a hesitancy in you fully embracing this subjective aspect of 'Zoe designing', and I guess I'm being selfish (very Yoko) and saying, 'YES, it is about YOU' in your approach to your research.

I think your work is worthwhile and very very interesting to many design practitioners in communication design, and will make a great contribution to the future of the practice. Talk more soon...

;-)

Yoko

Thanks so much for that fantastic response. There were a lot of things left unanswered in my presentation, with only 10 minutes to present I made a very broad stroke across a very large (and largely unformed) project. The "five points" structure was more of a presentation technique than an actual project plan, I am expecting to be working in a much more cyclical way (and be running on the spot at times), but until I begin discovering and reflecting, I can't predict where I will be moving next. My main self criticism of this outline is that it doesn't actually pose a question or problem - it states a topic area. This is because, at this stage, I'm not actually sure the direction I'm heading.

A lot of the points that you made are going to be really useful for me over the next couple of months when I start developing the approach to my 'generative phase'. I'll keep you posted!

I don't know you at all, but I stumbled upon your blog doing some internet research, and I've found that I'm a big fan of your topic. I was wondering whether you were able to locate any "high" and/or "low" critiques for Salvador Plascencia's "The People of Paper." I'm thinking of forming a project focused on the text, so any citations you could send my way would make me a very happy guy.

My email's whataplunge@gmail. Again, big fan of your topic.

Thanks,

Ben